The U.S. history of Native American Boarding Schools

(TW: abuse, sexual abuse, mental health, suicide)

Native American Boarding Schools (also known as Indian Boarding Schools) were established by the U.S. government in the late 19th century as an effort to assimilate Indigenous youth into mainstream American culture through education. This era was part of the United States’ overall attempt to kill, annihilate, or assimilate Indigenous peoples and eradicate Indigenous culture.

The Native American assimilation era first began in 1819, when the U.S. Congress passed The Civilization Fund Act. The act encouraged American education to be provided to Indigenous societies and therefore enforced the “civilization process".

The passing of this act eventually led to the creation of the federally funded Native American Boarding Schools and initiated the beginning of the Indian Boarding School era. The duration of this era ran from 1860 until 1978. Approximately 357 boarding schools operated across 30 states during this era both on and off reservations and housed over 60,000 native children. A third of these boarding schools were operated by Christian missionaries as well as members of the federal government. These boarding schools housed several thousand children.

Native American Boarding Schools first began operating in 1860 when the Bureau of Indian Affairs established the first on-reservation boarding school on the Yakima Indian Reservation in Washington. Shortly after, the first off-reservation boarding school was established in 1879. The Carlisle Indian School located in Carlisle, Pennsylvania was founded by Richard Henry Pratt. He modeled the boarding school off an education program he designed while overseeing Fort Marion Prison in St. Augustine, Florida. He developed the program after experimenting with Native American assimilation education on imprisoned and captive Indigenous peoples. Pratt served as the Headmaster of the Carlisle Indian School for 25 years and was famously known for his highly influential philosophy which he described in a speech he gave in 1892. He stated, “A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

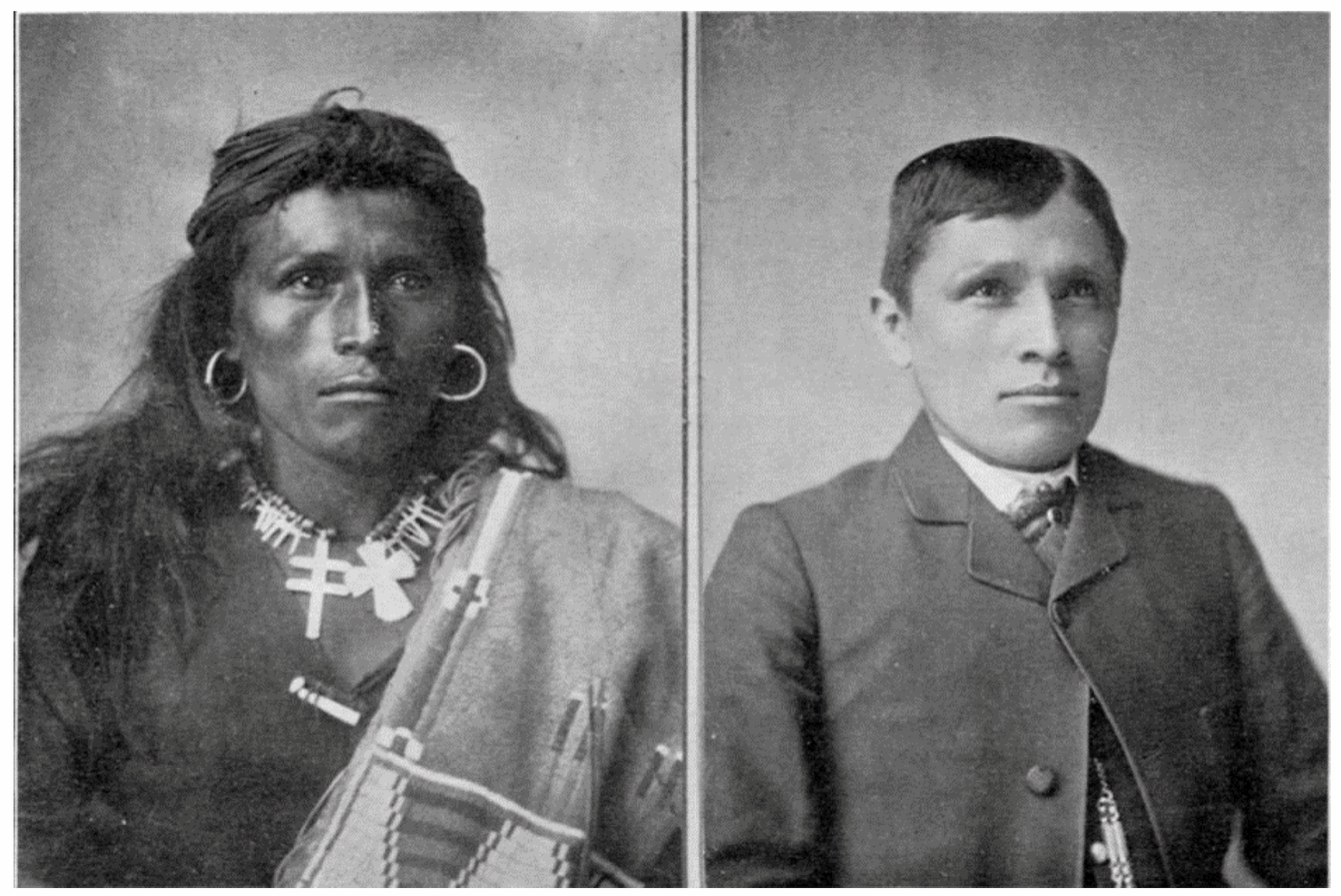

Attendance to the boarding schools was made mandatory by the U.S. Government regardless of whether or not Indigenous families gave their consent. Upon arrival, Native children were given Anglo-American names, bathed in kerosene, given military-style clothing in exchange for their traditional clothing, and their hair would be shaved off for the boys and cut into short bob styles for girls.

Education primarily focused on trades to make Native students marketable in American society. Male students were taught to perform manual labor such as blacksmithing, shoemaking, and farming amongst other trades. On the other hand, female students were taught to cook, clean, sew, do laundry, and care for farm animals. Standard academic subjects like reading, writing, math, history, and art were also taught, however, these subjects emphasized American beliefs and values. For example, students were taught the importance of private property, materialized wealth, students were forced to convert to Christianity, and celebrate American holidays such as Columbus Day. Richard Henry Scott eventually implemented a “Placing Out System” that placed Native students into American communities for a certain amount of time, varying from a Summer to a full year. These programs tended to exploit students and used them for domestic and physical labor.

Native students were not allowed to speak in their Native languages. They were only allowed to speak English regardless of their fluency and would face punishment if they didn’t. The discipline enforced at these boarding schools was severe. Punishments varied and included privilege restrictions, diet restrictions, threats of corporal punishment, and even confinement. Additionally, Native students were neglected and faced many forms of abuse including physical, sexual, cultural, and spiritual. They were beaten, coerced into performing heavy labor. Their daily regimen consisted of several hours of marching and recreational time consisted of watching disturbing movies such as Cowboys and Indians.

Since they were used as forms of punishment, food and medical attention were scarce. This led to boarding schools becoming more susceptible to infections and diseases like tuberculosis, the flu, trachoma. Due to these conditions, Native students would become ill and die at these boarding schools often. In 1899, a measles epidemic spread through the Phoenix Indian School, experiencing rates as high as 325 cases of measles in addition to 60 cases of pneumonia, and 9 student deaths within 10 days. Parents were rarely informed of their children’s deaths; some parents would learn of their child’s death after they were buried in school cemeteries. Some students were buried in unmarked graves. Those that survived these inhumane conditions were scarred from the traumatic experiences for the remainder of their lives.

Although a majority of Native children were forced to attend these boarding schools, some parents chose to send their children because those were the only schools available to their children. However, several forms of resistance were performed in response to having their children pulled from their homes and forced to attend these boarding schools. Some forms of resistance included entire villages refusing to enroll their children in the boarding schools, coordinated mass withdrawals, as well as encouraging their children to run away from the school. Indian agents – individuals hired to interact with Indigenous communities on behalf of the U.S. Government – would retaliate by withholding rations and supplies to Indigenous communities. These agents were also responsible for seizing children from their families and their homes until boarding schools were filled.

While the Native American Boarding School era has ended, the U.S. government still operates a few off-reservation boarding schools. As of 2020, 7 boarding schools continue to be federally funded, 3 of which are controlled by Indigenous community leaders. In 1934, the Indian Reorganization Act was passed to decrease U.S. federal control of Native affairs and instead allowed for Native self-determination and self-governance. An example of this transition can be seen with the Santa Fe Indian School which was established in 1890 and originally implemented the Carlisle model. By the 1920s, the school began transitioning after Indigenous leaders fought to gain control over the school. It is currently managed by Indigenous leaders where the focus has switched to traditional arts, sovereignty, Native cultures, and community.

Native youth still face several challenges within the American education system. They rarely have access to curriculums that are culturally relevant to them and experience difficulties in the classroom at alarming rates. According to reports given by the Kids Count Data Center and The National Violent Death Reporting System, Native students are:

1.2 times more likely to be behind in 4th-grade reading and 8th-grade math

1.4 times more likely to be suspended from school

1.5 times more likely to die in a homicide or suicide

1.7 times more likely to experience two or more adverse childhood experiences

1.8 times more likely to attend a high-poverty school

2.0 times more likely to drop out of high school

The tragedies Native children faced during this era have impacted the lives of not only the children but also their families and communities. These impacts have caused Indigenous communities to experience deep-rooted ramifications in regards to mental health and the overall relationship between Native communities and the American education system. They are often displayed in the form of poverty, difficulties in the American education system, poor physical health, and poor mental health. Many Native students who survived the boarding school era went on to suffer from mental health and other related issues such as anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, a lack of cultural identity, and the development of negative stereotypes (i.e. lazy, alcoholics, etc.), to name a few. These traumatic experiences have been passed down from generation to generation and continue to impact Indigenous communities today.

Documentaries

Unspoken: America’s Native American Boarding Schools (PBS Utah)

Unseen Tears: The Native American Boarding School Experience in Western New York, 2009 (Films for Action)

Literature

Code Talker: The First and Only Memoir By One of the Original Navajo Code Talkers of WWII by Chester Nez and Judith Schiess Avila

Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875-1928 by David Wallace Adams

They Called it Prairie Light: The Story of Chilocco Indian School by K. Tsianina Lomawaima

Pipestone: My Life in an Indian Boarding School by Adam Fortunate Eagle

Websites

Additional Book Recommendations from The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition

References

American Indian Relief Council. Native American History and Culture: Boarding Schools - American Indian Relief Council Is Now Northern Plains Reservation Aid, American Indian Relief Council, www.nativepartnership.org/site/PageServer?pagename=airc_hist_boardingschools.

Bear, Charla. “American Indian Boarding Schools Haunt Many.” NPR, NPR, 12 May 2008, www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=16516865.

Boone, Katrina. “America Has Always Used Schools as a Weapon Against Native Americans.” Education Post, Education Post, 13 Dec. 2018, educationpost.org/america-has-always-used-schools-as-a-weapon-against-native-americans/.

Elliot, Sarah K. “Antiques Roadshow.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, 13 Apr. 2020, www.pbs.org/wgbh/roadshow/stories/articles/2020/4/13/early-years-american-indian-boarding-schools.

Little, Becky. “How Boarding Schools Tried to 'Kill the Indian' Through Assimilation.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 16 Aug. 2017, www.history.com/news/how-boarding-schools-tried-to-kill-the-indian-through-assimilation.

Nabs. “US Indian Boarding School History.” The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, boardingschoolhealing.org/education/us-indian-boarding-school-history/.

Native Hope. The Issues Surrounding Native American Education, Native Hope, blog.nativehope.org/the-issues-surrounding-native-american-education.